Cardiovascular (Cardio)

Cardiovascular exercise is movement that involves large muscle groups in a rhythmic manner, such as walking, jogging, cycling, cross-country skiing, swimming. These exercises increase your heart rate. There are ‘cardio’ machines such as treadmills, elliptical trainers (that simulate cross country skiing movement – alternating simultaneous arm and leg movement), stepping machines and others, which all facilitate cardiovascular exercise.

Cardiovascular exercise requires the integrated functioning of many body systems, including increased breathing (ventilation), increased heart output (increased heart rate and increased flow per beat), increased blood flow through the circulation to the working muscles, and increased energy production by the working skeletal muscles. All this facilitates movement of oxygen from the atmosphere to the working muscles which use it for contractions and producing work.

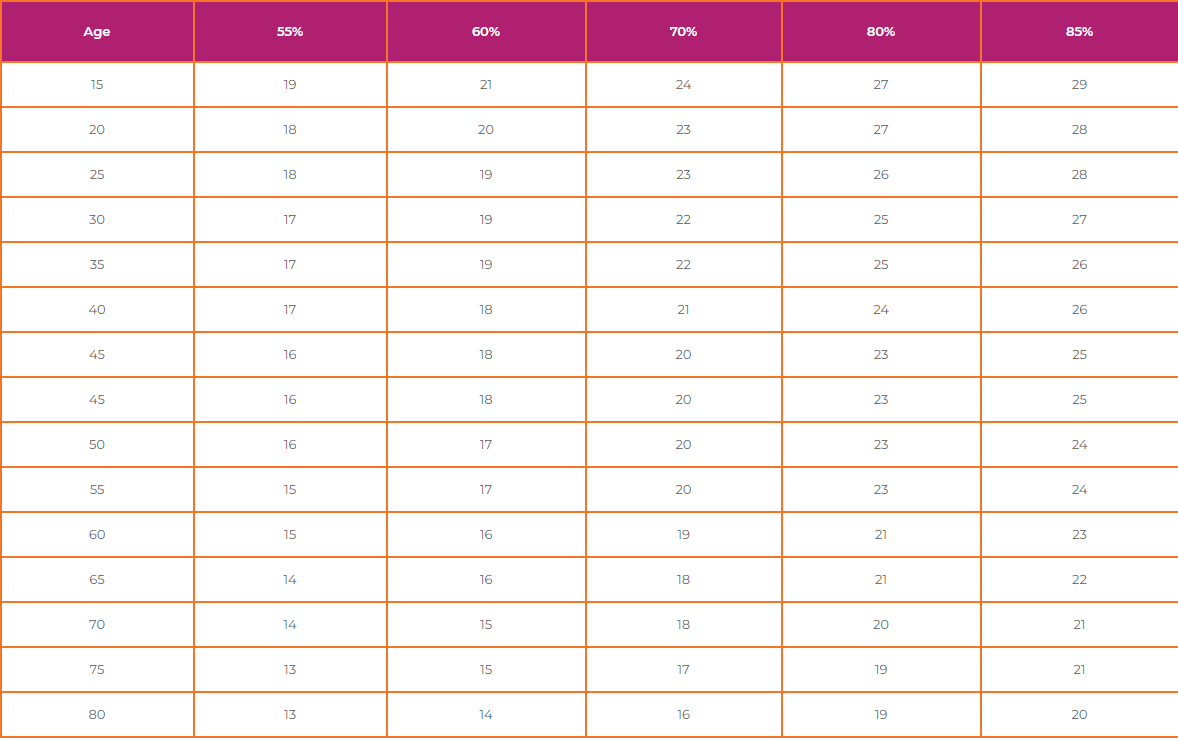

Exercise at lower intensity (exertion), uses primarily oxygen for energy production, however as the exertion increases above about 75% of maximal, some of the work is done without use of oxygen and a metabolic end product called lactic acid is produced and accumulates in the muscle, eventually causing muscle fatigue. Exercise below this threshold will be more easily sustained, and is less fatiguing. A good indicator that you are around this threshold is when breathing starts to become difficult.

Responses to cardiovascular exercise:

Cardiovascular exercise strengthens the heart muscle. It improves circulation to the muscles and increases the ability of the muscles to extract and use oxygen for energy production, so they can do more work. Normal responses to a single bout of cardiovascular exercise include: increase in breathing rate and depth, increase in heart (pulse) rate, increase in systolic blood pressure and no change or lowering of diastolic blood pressure, increase in blood flow to the working muscles and away from nonworking tissue (i.e. digestive track). If the exercise intensity (speed, resistance, or both) increases, these body responses gradually grow until maximal levels of exercise are achieved, at which point, the exercise cannot be continued. Pushing the effort to maximal levels is not recommended for general conditioning, since these levels are not sustainable for the recommended duration of time. This will result in fatigue and possibly muscle soreness that may prevent exercise the next day. Those wishing to train competitively may include high intensity interval training as part of their conditioning program for their sport, however, with higher intensity exercise there is a greater risk of musculo-skeletal injury.

Through increased stimulation of the heart, circulation and muscles, with regular exercise, the body adapts and progress is made. Thus, following a period of 3 months of regular exercise training, changes observed would be lower heart rates at rest, and during exercise at a given level (i.e. walking 3.0 miles per hour on a treadmill), breathing would be lower, heart rate will be lower, blood pressure will be lower, and the work will feel easier (perceived exertion). Thus, before starting a program of cardiovascular exercise, an inactive person may have difficulty climbing stairs and experience significant shortness of breath, increased heart rate, and leg fatigue and have to stop and take a rest. After consistent exercise, climbing this same flight of stairs will become easier, with less breathing required, a lower heart rate, and less muscle fatigue (due to increased muscle strength, increased blood flow to the muscles and more efficient use of oxygen by the muscles), thus physically, things will become easier to do.

Strengthening: Weights and Toning

To strengthen specific muscles, it is important to work both individual muscles and their surrounding muscle groups. By exposing the muscles to progressive resistance either with your own body weight, moving against gravity for resistance, or using weights (hand weights or machines), elastic bands. There are different types of programs and ways to gain muscle strength, depending on your starting point and your goals. For most people who have lost significant muscle strength and are starting at a low level of activity, it is sensible to use lighter weights, lifting them more times (higher repetitions). If you are interested in more competitive sport participation, using higher weights with fewer repetitions would be appropriate, as long as those individuals have a good baseline level of strength to start with. Organ transplant recipients can definitely increase their muscle strength, although it is possible that some immunosuppression medications may slow strength development when compared to others.

The principle of start slowly and progress gradually is critical in developing strength. There are structural changes that must occur within the muscles when starting and progressing with increased resistance in order to achieve strength gains. Too much resistance or too great of an increase in resistance without allowing adaptation can damage muscles and delay any strength gains. Starting slowly and progressing gradually will also minimize muscle soreness.

Double-lung recipient Kate Phillips

Flexibility

Muscles that are unused and weak also become stiff and stunted. In order for optimal performance, muscles must be lengthened and have the ability to stretch and move freely. Specific stretching exercises for individual muscles and muscle groups are an important part of an exercise program and developing fitness. The principle of start slowly and progress gradually applies to the stretching exercises outlined below also.